If you’ve been to the Hawaiian Islands, chances are high you were enraptured by its copious beauties, from dizzying cliffs riven waterfalls to sun-drenched shores that sparkle with perfection.

But in addition to Hawaii’s sensory delights, vacationers unfamiliar with the Aloha State are often surprised—pleasantly and otherwise—by the islands’ surplus of modern conveniences: big box stores, chain restaurants, mega-resorts, and malls large enough to rival the mainland’s. And if you don’t get out of the center of big cities or towns, you may ask “where is the old Hawaii”—the place of swaying palms, traditional customs, and deserted beaches?

Visitors, of course, aren’t alone in bemoaning this. Indeed, beneath the glitz and thrills of contemporary tourism exists the sorrow of Hawaii’s history.

In the late 18th century, the King of England ordered Royal Navy Captain James Cook to sail off in search of terra australis incognita—an enormous though fabled continent thought to rest in the South Pacific. Instead, the bold voyager came upon New Zealand (which was first discovered by Abel Tasman in 1642) before accomplishing the first recorded European contact with Australia—and, later, an isolated and stunningly gorgeous archipelago he crowned the Sandwich Islands.

While Cook met his demise after a skirmish with Hawaiians on February 14, 1779, his “discovery” of Hawaii ushered in a shift that would permanently alter the state of the islands and its people.

Hawaiians arrived long before Cook set out blind into unchartered waters. Debates abound around the actual settlement of Hawaii, but a number of archeologists agree that Polynesians from the Marquesas struck the islands’ shores in double-hulled boats in 700 A.D. From there, Polynesians—fortified with canoe crops and a polytheistic religion—flourished in the fertile, exotic land, ultimately building a culture that would prove to be, in many ways, unflappable.

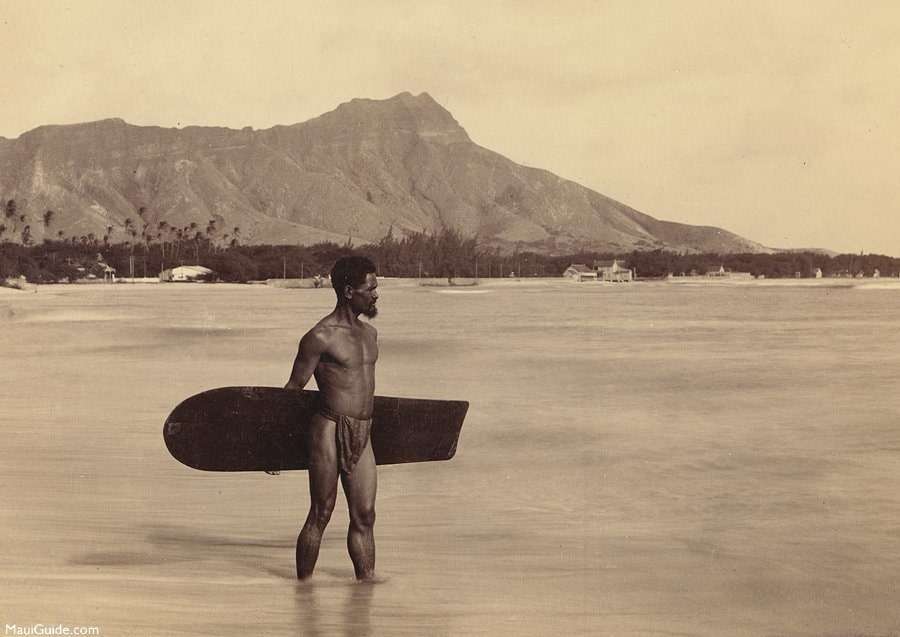

Cook’s discovery of the islands and his subsequent death was followed with what’s become known as the arrival of Western Contact—an era marked by the influx of New England Calvinist missionaries and the lasting imprint Cook’s arrival had on Hawaii. With this also arrived the enduring effects of colonialism. Traditional Hawaiian customs—surfing on olo boards carved from koa and wili wili trees and dancing hula among them—were rendered taboo due to their suggestiveness (he’e nalu, or surfing, was performed, for example, in the nude).

The Hawaiian language—long a dialect that evolved (and survived and thrived) through oral traditions—was recorded into a written patois that was, in the end, effectively decimated through the influence of Protestants. Disease—chiefly smallpox—assailed the islanders in spades, annihilating the Native Hawaiian population from roughly 300,000 in the 1700s to 60,000 in the mid-19th century to a mere 24,000 in 1920. And, galvanized by the introduction of the “white man’s” weapons—cannons and muskets, as well as Western war tactics and assistance from British soldiers—the King of Hawaii, Kamehameha the Great, unified the islands, save for Kauai and Ni’ihau, in a bloody sweep that left countless natives dead.

In the years that followed, the Hawaii that had been known by the Polynesians radically changed. Kapu—an ancient form of cultural restriction—was lifted, steering in a dramatic shift in the islanders’ approach to living and social customs. Its feudal structure turned into a modern constitutional monarchy that was ultimately abolished. Hawaii’s capital, upon persuasion from Westerners, was moved from Maui to Oahu, thus foreshadowing the end of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Invasive species—metaphorical and literal—took root, first with the introduction of goats, horses, cattle, and non-native plants, and later with the advent and proliferation of sugarcane and whaling. Meanwhile, the language faded in favor of English and Pidgin, an interethnic vernacular borne from the mix of plantation workers, their overseers, Native Hawaiians, North Americans, and cowboys who were commonly known as paniolo.

The rest of the world mirrored Cook’s original awe. Not only was the land utilized to cultivate sugar—ultimately turning Hawaii into one of the biggest suppliers of sugar—but the plantations that first began on the island of Lanai, coupled with The Great Mahele (a land division law set forth by King Kamehameha III), misplaced Native Hawaiians from their ‘aina. Steamships arrived in droves. The population increased by 337,000 over the course of a single decade, due to the deluge of laborers. Subsistence farming long relied upon by Hawaiians—kalo (taro), banana, fish ponds, and more—began to disappear to make room for the burgeoning industry. English-centric schools were built. The U.S. government noted Hawaii for its strategic position in the Pacific, first leasing Pearl Harbor before Congress formally annexed Hawaii in 1898.

By the time Hawaii became the 50th state in the Union in 1959, its racial demographic and aloha way of life had been fundamentally altered; in 2015, Native Hawaiians made up a scant 6% of their original home’s population.

These facts laid bare here would readily suggest that Cook’s “unearthing” of the islands has been nothing but calamitous.

And so it is true, in myriad ways. The landscape, as discussed, has been forever changed in what many deem “cultural genocide.” (To phrase the above differently, 1 in 7 Native Hawaiians died within two years of Cook’s arrival, whose men introduced, in addition to smallpox, polio, measles, chickenpox, and tuberculosis.) Hawaiians today live in the shadow of that imperialism, upon which National Geographic, following the story of Richard “Buffalo” Keaulana (a “rare full-blooded Hawaiian who has spent most of his 80 years on Oahu’s West Side”), writes, “The bitter legacy of colonization left an indelible stamp on Hawaiians of Keaulana’s generation. He spent his childhood in poverty, much of it on state-provided ‘homestead’ land—Hawaii’s version of an Indian reservation—in the West Side community of Nanakuli. The native language had been purged from public schools in favor of English, though in practice the locals spoke pidgin, an English-based creole still common in the area.” Others report an inborn resentment towards haoles (foreigners), with news of racially-motivated attacks against visitors and non-Hawaiian residents surfacing weekly. The last day of school in Hawaii has long been known as “Kill Haole Day.” Protestors interrupted a statehood celebration in 2006 by calling out racial slurs. The hostility, even hatred, some Native Hawaiians feel towards haoles is described by the Dean of the School of Social Work at the University of Hawaii Jon Matsuoka as “ancestral memory.”

“That trauma is qualitatively different than with other ethnic groups in America. It’s more akin to American Indians because Hawaiians had their homeland invaded, were exposed to diseases for which they had no immunity, and had an alien culture forced upon them.” Cruelty aimed at whites in Hawaii, Matsuoka says, “is minor compared to the larger issues underlying it.”

“The Hawaiian spirit of Aloha is pervasive, but you have to earn aloha. You don’t necessarily trust outsiders, because outsiders (historically) come and have taken what you have. It’s an incredibly giving and warm and generous place, but you have to earn it,” he says.

University of Hawaii Hawaiian Studies professor Haunani-Kay Trask sums it up as such in her book, From A Native Daughter: “Just as … all exploited peoples are justified in feeling hostile and resentful toward those who exploit them, so we Hawaiians are justified in such feelings toward the haole. This is the legacy of racism, of colonialism.”

And yet, the detestation for Cook and the missionaries that followed isn’t felt across the board. Many point to the fact that Hawaii would never have been able to remain in isolation as the world continued to progress; whether it be Cook or George Vancouver, the islands’ discovery was outright inevitable. Others still point to the conviction that Western contact brought some good to Native Hawaiians: it ended a patriarchal and ferociously hierarchal society that forbade women from eating in public spaces, separated them from the community during their menses, and favored the ali’i (or royalty) over commoners (to say nothing of the disenfranchised). As Hawaii History writes, Cook brought “destruction, disease, and death” but he (and the era) also brought “opportunities, admiration, and sharing.” In short, some believe it paved the way for a fair republic that enhanced Native Hawaiians’ safety, health, and education.

No matter where one stands on the issue, Hawaiians today are at the forefront of a major resurrection of their culture, while their population is beginning to flourish again.

Data from the Pew Research Center demonstrates that “the Native Hawaiian population in the state and across the country has been surging, and growth is projected to continue…The total Native Hawaiian population (which currently stands at 298,000) is projected to reach more than half a million by 2045 and more than 675,000 by 2060, according to a 2012 report by Kamehameha Schools”—numbers that align with state estimates published in 2010.

In addition, the hanai system in which individuals and families informally adopt others and provide them with everything from food to advice also continues to prosper. Two Hawaiian Renaissances are often referred to—the first began under the reign of King Kamehameha V; the second began in the 1970s and continues to prosper today—to demonstrate that the Hawaiian culture will persevere through the renewed interest in the Hawaiian language, hula, crafts, music, rituals, studies, and ancient voyaging. (Think here of the Hōkūle‘a.)

Further, the Constitution of 1978 prompted the development of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (a “semi-autonomous” department of the State of Hawaii that was built to oversee the Hawaiian Homes Commissions Act, shield Hawaiian rights, uphold traditions, and improve the lives of Native Hawaiians) and enabled Hawaiians to reclaim federal land, like the island of Kaho’olawe (which was once used as a bombing range and training ground by U.S. Armed Forces). As George Kanahele wrote in 1979, “Let me say, first of all, we’re not really here to listen to me talk about the Hawaiian Renaissance—we’re here to celebrate it. For if anything is worth celebrating, it is that we are still alive, that our culture has survived the onslaughts of change during the past 200 years. Indeed, not only has it survived, it is now thriving. Look at the thousands of young men dancing the hula; or the overflow of Hawaiian language classes at the university; or the revived Hawaiian music industry; or the astounding productivity of Hawaiian craftsmen and artists…Like a dormant volcano coming to life again, the Hawaiians are erupting with all the pent-up energy and frustrations of people on the make. This great happening has been called a “psychological renewal,” a “reaffirmation,” a “revival” or “resurgence” and a “renaissance.” No matter what you call it, it is the most significant chapter in 20th-century Hawaiian history.”

We may be in the 21st century now, but Kanahele’s statements continue to resonate. As Mauian and Founder of Na Wahine Ho’omana says, “Queen Liliuokalani’s and the ancient Hawaiians’ ethos will always persist. Hawaii is about loving the land and loving its people, and no Westerner has been or will ever be able to change that.” To which we say, hana hou—and mahalo.

This article was researched and written by Maui residents from Maui Guide. With an ever-changing world, the writers and photographers at Maui Guide are working hard to share their home along with its history and unique culture.